The dramatic decline of vultures remains one of the poignant stories of wildlife conservation in India. The primary reason was a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory veterinary drug (NSAID), diclofenac. Being a pervasive drug, diclofenac would remain in cattle even after their death and be indirectly consumed by vultures, which then suffer fatal consequences. Consumption of diclofenac caused gout and kidney failure in three species of Gyps vultures; White-rumped (Gyps bengalensis), Long-billed (Gyps indicus), and Slender-billed (Gyps tenuirostris) vultures which suffered the highest levels of mortality with a >98% decline in their numbers, and indeed already 99.9% declines for the white-rumped vulture. These species are currently listed as Critically Endangered under the International Union for Conservation of Nature and are included as Schedule I species under the Wildlife Protection Act (WLPA, 1972).

Among the steps taken, there are major ex-situ conservation measures underway at several centres in India to breed and replenish populations of the three species in the wild. These sites are in Assam, Gujarat, Haryana, Madhya Pradesh, and West Bengal. The majority of these are managed by dedicated teams and experts of the Bombay Natural History Society together with the respective state forest departments.

Recently, Saving Asia’s Vultures from Extinction (SAVE), a consortium of 24 partner organisations, held their 11th annual meeting to discuss progress and priorities for vulture conservation in South and Southeast Asia. During the talks, it was evident despite the efforts to reinstate numbers, challenges in the wild remain, especially the widespread veterinary use of toxic NSAIDs. The sale of diclofenac was banned in India, Pakistan, and Nepal since 2006, but the implementation of the ban in India has not fully succeeded in removing the drug, and indeed there are several more toxic drugs, especially aceclofenac and nimesulide which are increasingly being used by vets. Thus, the state of recovery of vultures has been slow. Bangladesh has become the first country in the world to ban the drug ketoprofen, another veterinary drug known to be fatal to vultures when consumed. On the positive side, safe alternative drugs have also been identified, notably meloxicam and more recently tolfenamic acid, but these have not fully replaced diclofenac, and it is the other NSAIDs that have proven to be toxic (like diclofenac) that require urgent attention if vultures are to persist. The Indian Veterinary Research Institute (IVRI) in collaboration with the Bombay Natural History Society and Royal Society for the Protection of Birds led a study to ascertain the impacts of tolfenamic acid and safety testing of this drug on vultures in an ex-situ breeding site in Haryana. Such a study is significant for vulture conservation if it helps decision-makers to remove toxic drugs and promote the use of safer alternatives instead. In some areas like Assam, cases of accidental poisoning are also reported due to poison baits targeting dogs and other problem mammals. Strict regulation on the distribution of diclofenac, aceclofenac, nimesulide and ketoprofen in rural cattle populations and better awareness of the misuse of pesticides remain the only way to arrest further depletion in vulture populations.

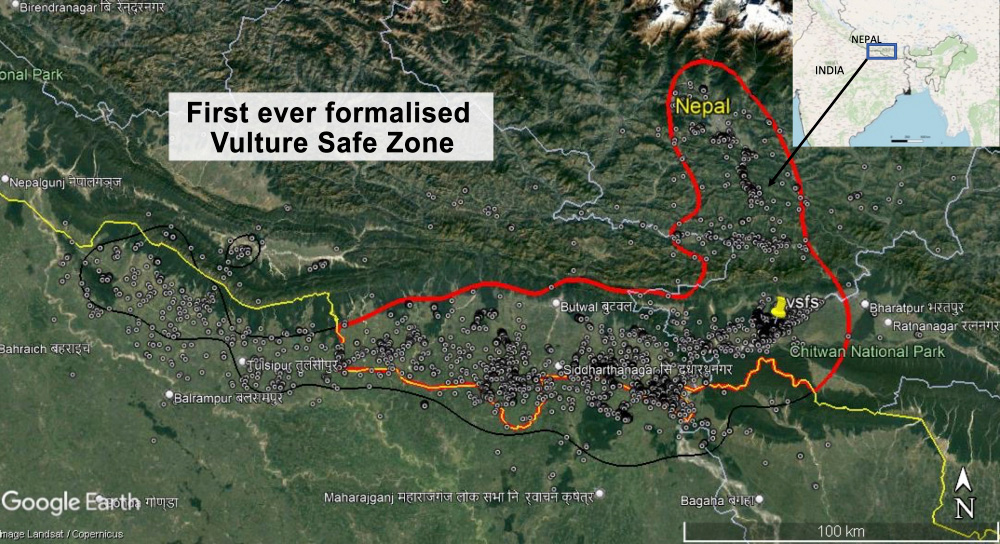

However, there have been recent notable successes. The first-ever fully ‘vulture safe zone’ (VSZ) was declared in Nepal in the Gandaki- Lumbini VSZ at the recently concluded 11th annual meeting of SAVE. A VSZ is an area where the use of diclofenac has been completely stopped, and tagged vultures proved to be surviving well within a radius of around 100 kilometres around a present breeding colony, thereby demonstrating that the risk of poisoning of vultures by NSAIDs or other reasons has been addressed in the area.

The boundary of the VSZ in lowland Nepal (red) close to the Nepal-India border (yellow). The area in the black contour is the home range of the tagged vultures.

This success has been linked directly to Nepal’s effective removal of the toxic drug diclofenac from veterinary use and initiatives at national, regional, and local government as well as community levels on the hazards posed by these drugs to vultures. Vulture Safe Zones initiatives are underway in India as well. Examples are in Bundelkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat, Majuli Island in Assam, Terai areas in Uttar Pradesh and another one is being mooted in Karnataka.

Subsequently, establishing more such vulture safe zones would help retain a natural population in addition to being able to safely release captive birds back to the wild. But most importantly, this means state and national governments taking effective measures to remove those dangerous veterinary drugs. Establishing more VSZs and testing their safety is only possible, as outlined by SAVE, by intensive satellite tagging of wild birds or extensive testing of cattle carcasses throughout the area for toxic drugs, encouraging more safety testing by the IVRI of safe drugs on vultures and pharmacy surveys of available NSAID drugs stocks. Such sustained efforts for regulating toxic drugs and creating more vulture safe zones as stated in the Indian Government’s 5-year vulture action plan are the way forward to achieve the goal of restocking vulture populations back into the wild and replicating the successful efforts of neighbouring Nepal.

CI is a non-profit, non-commercial portal that aims to facilitate wildlife and nature conservation by providing reliable information and the tools needed to campaign effectively.

CI is a non-profit, non-commercial portal that aims to facilitate wildlife and nature conservation by providing reliable information and the tools needed to campaign effectively.