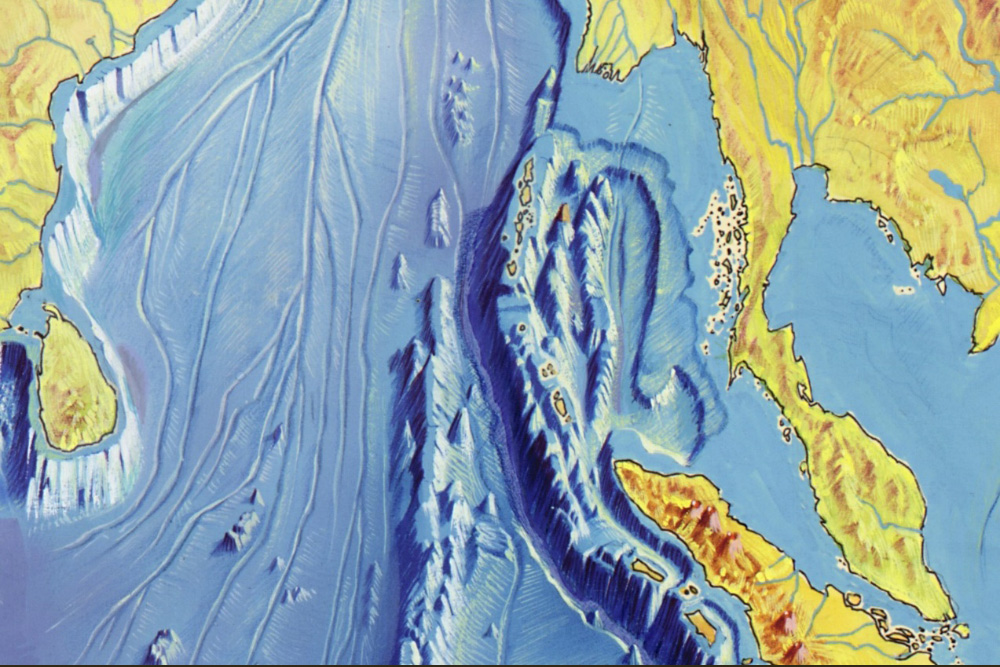

The Andaman & Nicobar Islands lie between the Andaman sea and the deeper Bay of Bengal and are the peaks of a subsurface mountain range known as the Andaman and Nicobar Ridge. The islands are situated on the great tectonic suture zone that extends all the way from the eastern Himalayas in the north to Sumatra in the east and the Lesser Sundas in the south. The geographic features of the sea-floor in this region leads one to wonder about the kind of life these undersea mountain ranges might be home to.

Cetaceans are no strangers to these waters, which are a part of the North Indian Ocean Whale Sanctuary. This protected zone was established in 1979 by the International Whaling Commission to ban commercial whaling in the Northern Indian ocean. Despite this status, there has been little scientific documentation of cetaceans from the A&N region, with records restricted to sporadic sightings and beachings. Dating back to 1933, 9 species of cetaceans were documented from these waters. The first cetacean survey, however, was carried out by marine explorer, Stephen Leatherwood, in 1983. Yet, photographic evidence and detailed species descriptions are scant.

While reviewing the literature, I came across the work of researchers Anoukchika Ilangakoon and Abigail Alling, who had undertaken a fifteen-day sea voyage from Singapore to Sri Lanka, in December 2012, to document cetaceans encountered during their journey. While the idea of hopping onto a boat to go surveying was exciting, I realised that, given the extensive spread of these islands, and the little baseline information available, there was quite a bit to be done before heading out to sea.

So instead, I decided to talk to those who spend a good part of the year, perhaps even their lives, at sea, and learn from them. In this way, keeping the place, its people, and our pocket in mind, we adapted and developed methods that helped us get a glimpse into the lives of the cetacean species inhabiting these waters.

My interactions with fishers most often took place in their villages. Whether in the Bengali settlements, golden in hue with their dung swept yards and mud houses nestled among neat rows of areca trees, or the villages of the Andhra fisherfolk, with their brightly painted walls and the ever-present whiff of dried fish, I was reminded of the villages I had seen back on the mainland.

Clutching a stack of datasheets with a few dozen questions, a catalogue of cetacean photos and a few maps, I’d spend days walking through villages talking to people about dolphins and whales. Through these surveys, I wanted to piece together the diversity, distribution and seasonality of cetaceans in the Bay of Bengal and the Andaman Sea. But with time, I also found myself becoming interested in understanding how these communities perceived these animals.

During interviews, they would sometimes show me photos or videos or just vividly describe their observations. At Burmanallah, a fisher excitedly described a species of dolphin known locally as ‘Shaktimaan’, after the eponymous Indian superhero. This, I learned, was an apt description of spinner dolphins (Stenella longirostris). Another description was of a mountain that rises out of the water, stays afloat for a few minutes, and lets out a ‘phauvaraa’ (a jet of water) before gently sinking back in – which was reminiscent of the rafting behaviour of sperm whales (Physeter macrocephalus) before a dive.

Apart from the commercial fishers, a niche community of recreational fishers based out of the islands also helped shape this study. Not bound by the land-in-sight constraint that most of the former face, these sport fishers, with their sophisticated navigation systems and high-speed boats, are able to go further and explore offshore habitats, seamounts, and oceanic banks, and thus end up seeing much more.

A surprising find turned up when my advisor, Dipani Sutaria, and I, were looking through photos shown to us by Akshay Malavi, a sport fisher who has been sailing these waters for more than a decade. Among them was one taken by him right outside the Port Blair harbour in 2015: a tall, curvy dorsal fin set on a deep grey back – most likely a baleen whale. Finding baleen whales in these waters had always been a topic of debate because the A&N Islands are not along any known migratory routes, and no previous records of them existed from these waters. Akshay’s documentation settled it once and for all.

In this way, sometimes through almost mythical descriptions, and sometimes through keenly taken photographs, I put together the information that became the basis of my study. Whether through Akshay’s documentation, or Darran letting me piggyback on fishing trips where I witnessed feeding frenzies of hundreds of dolphins, it was the islanders’ generosity that helped me piece together the occurrence of cetacean species and their likely habitats in the Andaman sea.

The islands also offered another convenient yet important platform for me to conduct surveys and make first-hand observations – the inter-island ferries that traversed the length of its east coast. From witnessing a galloping army of Fraser’s dolphins (Lagenodelphis hosei) to having the more elusive Dwarf sperm whale (Kogia sima) surface right at the bow, to seeing an orca (Orcinus orca) breach while trying to stun a school of fish, these ferries proved to be as much a life-line for the study as they are for the people living on the Islands.

The study thus ended up using three approaches – community interactions, a citizen science network, and first-hand observations made from ferries, and a fishing boat. Through these, we learnt that the sea here, with its deep canyons, steep drop-offs, seamounts and oceanic banks, has helped shape a community of at least 15 cetacean species. Of these, the Omura’s whale (Balaenoptera omurai), a baleen whale, and Fraser’s dolphins were documented in these waters for the first time.

But we learnt more than this. Through free-flowing conversations with island folk, we also gleaned ecological clues on patterns of space-use and seasonality that have helped shape newer hypotheses, which are foundations for future work.

CI is a non-profit, non-commercial portal that aims to facilitate wildlife and nature conservation by providing reliable information and the tools needed to campaign effectively.

CI is a non-profit, non-commercial portal that aims to facilitate wildlife and nature conservation by providing reliable information and the tools needed to campaign effectively.