What is a corridor?

In the sphere of conservation biology, a wildlife corridor is a strip of habitat that connects two wildlife source populations and serves as a movement path for wild animals in search of resources such as food, habitat and mates. In a larger landscape, consisting of many source populations, one can have a network of corridors, connecting pairs of source populations so that they are connected directly or indirectly. Together these populations constitute a metapopulation.

For several reasons, small isolated populations are more susceptible to local extinction. Many would have heard about the disappearance of tigers from well-known tiger reserves due to poaching. Small isolated populations of animals also become locally extinct due to natural population fluctuations. In addition, inbreeding of isolated populations for long periods cause a loss of genetic viability. Corridors allow recolonization of sites where the population is locally extinct and reduce the danger of inbreeding. Corridors are especially important for large, landscape animals such as tigers, dholes, leopards and elephants. The 2006 amendment of the Wildlife Protection Act recognises the importance of corridors and gives them special protection.

Types of corridors

Corridors may be broad and continuous, or they may be narrow. Some corridors are fragmented or broken by a gap in the corridor. Small “stepping stone” habitats can be important for bridging the gap.

For landscape species, such as tigers and elephants, corridors can be several kilometres, or tens of kilometres, long. Besides forested corridors, tigers and leopards move across sugarcane fields, since these provide cover throughout the year. Elephants move across large expanses of the agricultural landscape. However, forested corridors are considered important for the dispersal of wildlife.

Problems affecting corridors

The integrity of corridors is affected by many factors including forest health, human presence and developmental activities. Human development such as the growth of urban centres and the growth of rural populations gradually eats away at corridors. Encroachment creates fragmentation of corridors. Tree cutting and fire degrade the habitat in corridors. All these issues need to be addressed to protect corridors. Linear infrastructure such as roads, railways, canals and electric lines cut through corridors and create barriers to the movement of wildlife within corridors. In such cases, mitigation measures such as underpasses and overpasses are necessary for the movement of animals.

Occupancy Survey in Melghat-Satpura Corridor

Traditionally wildlife presence was monitored by estimating its population – also known as a census. This is a very labour-intensive process. Nowadays an alternative technique, known as occupancy, is used for monitoring wildlife populations. By this technique, the probability of the presence of a species is estimated by making repeated visits to a site to record its presence or absence in each visit.

Melghat Tiger Reserve, located in the Amravati District of Maharashtra, is home to about 46 tigers, while Satpura Tiger Reserve, located in the Hoshangabad District of Madhya Pradesh, supports a population of 42 tigers. The two tiger reserves are connected by the Satpura-Melghat Corridor. Together this landscape is estimated to support about 100 tigers. The Satpura-Melghat Corridor lies mainly in the Satpuda Hill Range and is spread across a vast area of 9,000 sq. km. The terrain in the corridor is hilly and rugged and the habitat consists mainly of the dry deciduous teak-bearing forest. The landscape harbours a variety of large mammals, that includes carnivores like tiger, leopard, dhole, sloth bear, and herbivores such as gaur, nilgai, sambar, muntjac, four-horned antelope and wild boar. Villages of tribal communities such as Korku, Gond, Yadav, Gawli and Pardhi communities are dispersed throughout the corridor. These tribes are economically marginalised. Though they are primarily agricultural communities, they depend considerably upon forest resources such as firewood, fodder for cattle, and Non-Timber Forest Produce (NTFP) such as tendu patta, mahua, awla, chironji and honey for livelihood.

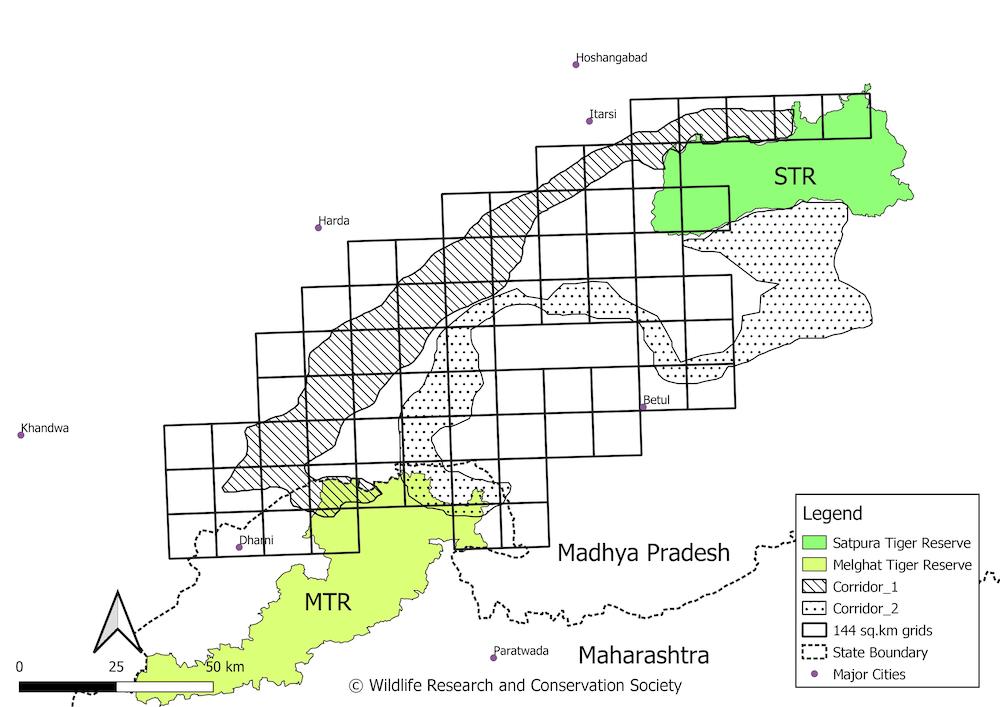

Wildlife Research and Conservation Society (WRCS) has been working on tiger conservation in Melghat Tiger Reserve for many years. Considering the importance of this corridor for tiger conservation, we planned a survey to study the distribution of major wildlife species and their occupancy in the corridor and study the threats and problems for tiger conservation in the corridor. With this aim, our team, led by Pavan and Kaushal, surveyed the Melghat-Satpura corridor from October 2020 to June 2021. We were helped in the survey by several volunteers, who participated in the survey in batches of two or three at a time. We received tremendous support from the Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra Forest Departments, who allowed us the use of their forest rest houses, and their frontline staff accompanied us on forest trails during the survey. WWF-India helped us in the design of the survey and analysis of the data. We started our survey from the buffer zone of Satpura Tiger Reserve and gradually moved southwards through the forest divisions of Hoshangabad, Harda, North Betul, South Betul, West Betul and Khandwa, till the Maharashtra border. In Maharashtra, we surveyed Melghat territorial division and buffer zone of Melghat Tiger Reserve.

The entire corridor area was divided into a grid of 144 sq. km. cells which were subdivided into smaller cells of 36 sq. km. and 9 sq. km (see map). The survey was carried out by walking trails of 10 km length every 36 sq. km. cell. Along each trail, the team made detailed observations of wild animal presence based on signs such as scat, dung, tracks, scrapes, scratch marks, digging signs etc. Simultaneously, they recorded information on the habitat, terrain, and human-related threats such as tree cutting, fire, human presence, linear constructions and vehicular activity. We conducted interviews with forest officers and local communities in each forest that we surveyed, to understand their issues and problems, and their interaction with the forests and wildlife.

Main findings

Through the survey, we came across many signs and direct sightings of wild animals. The most common large carnivore was the leopard, followed by the sloth bear. Tiger signs were found in all divisions, but they were uncommon. In the dense forest patches of North Betul and Hoshangabad divisions, we found a fairly good presence of dholes (Asiatic wild dogs). Among the herbivores, muntjac (barking deer), and blue bull were the most common species followed by sambar. Although large wildlife species are fairly well dispersed in the corridor, the chances of sighting them are slim because of their low density. Hyena, wolf, and four-horned antelope were found rarely and were confined to particular areas in the corridor.

Our only sighting of a tiger was at the beginning of the survey, at Churna in Satpura Tiger Reserve. In the evening, when the team was returning from a trail, we saw a huge male tiger. In Jamai, Sarni and Amla range in Chhindwara and Betul Districts, we learnt about a radio-collared tigress that was being tracked by the Forest Department. We heard reports of a tiger travelling through sugarcane fields in Udadan village in North Betul Division. It hunted cattle for a few days in a neighbouring village before moving on to Betul Range. This information supported reports of tigers using sugarcane fields as habitat in the Terai region.

The interviews with communities led us to believe that people living near forests are not against the presence of wildlife, but rather are more concerned with the livelihood issues faced by them. One of the major issues faced by people across the landscape was water scarcity.

The main problem related to wildlife presence was crop damage by wild herbivores. While there were reports of cattle kills by wild animals, the number of cases was not high. Sloth bear attacks were reported in all areas of the corridor and human injuries were common. Human deaths due to tiger attacks were rare.

The connectivity of the corridor is adversely impacted by national and state highways, railway lines and high-tension power lines crossing the corridor. These linear infrastructures prevent the free movement of wildlife across the corridor and cause wildlife mortality due to accidents when animals try to cross them. . The main obstructions are caused due to national highways NH46 and NH47, state highway SH26, and the Nagpur-Bhopal, Itarsi-Jabalpur and Itarsi-Mumbai railway lines. Underpasses and overpasses across highways and railway lines are generally recommended to enable the movement of wild animals. The lack of underpasses has been brought to the attention of the highway authorities by conservationists and it is hoped that remedial action is taken on this soon.

Tree cutting by local people for firewood and timber was a common problem throughout the corridor. At a few places, tree felling was also carried out by timber-cutting gangs. Forest fires were common during summer. Often these fires were accidental, due to the burning of agricultural waste, which escaped into the forest. Forest fires were reportedly caused by some local people for better grass in the next season, or for better sprouting of tendu leaves, which are collected for making beedis. Encroachment on forest land was observed occasionally. Cattle grazing was prevalent throughout the corridor – herds of cattle were often seen in the forest unaccompanied by a grazier. The growing population and expansion of villages and urban centres pose a serious problem, leading to deterioration and fragmentation of corridors.

The main focus of territorial forest divisions in the corridor is forest protection and timber production. It is necessary to strengthen wildlife conservation as an agenda of the territorial divisions in the wildlife corridor. Our survey will provide detailed information on wildlife presence in the corridor, and identified the main issues and problems, which will help the Forest Department in the conservation of the corridor.

Acknowledgements

This occupancy survey in the Satpura-Melghat corridor was enabled by a grant from US Fish and Wildlife Service.

CI is a non-profit, non-commercial portal that aims to facilitate wildlife and nature conservation by providing reliable information and the tools needed to campaign effectively.

CI is a non-profit, non-commercial portal that aims to facilitate wildlife and nature conservation by providing reliable information and the tools needed to campaign effectively.