Illegal wildlife trade (IWT) is a major threat to numerous wildlife species and ecosystems across the world, with established global links to organised criminal activities and an annual value encompassing billions of dollars. Media reports function as an untapped reservoir of publicly available records that can be utilised to understand the nature and scale of this trade.

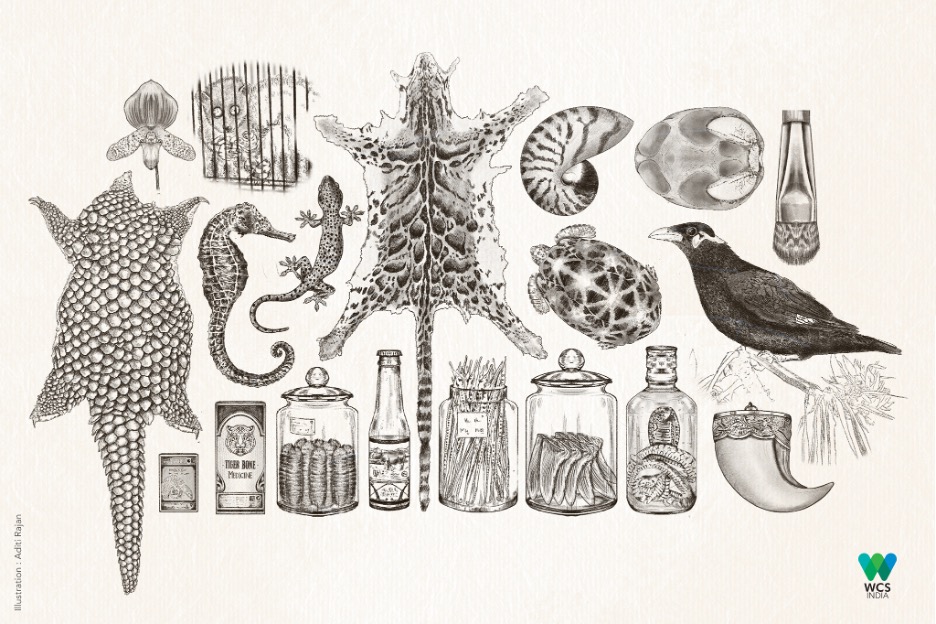

A report, “Media-Reported Wildlife Poaching and Illegal Trade in India 2020,” was published by the Wildlife Conservation Society-India. It provides a comprehensive overview of illegal wildlife trade based on online open-source newspaper articles, documenting instances of poaching and illegal trade from January 1, 2020, to December 31, 2020. The team collated 522 unique wildlife poaching and trafficking incidents using online search engines and open-source media records for the year 2020. The records were classified into broad categories such as big cats (tiger, leopard), ungulates (deer, antelope, boar, wild sheep), and pangolins (Indian pangolin, Chinese pangolin), among other species groups, which were used to identify spatial, temporal and species-specific patterns.

However, certain limitations of this exercise need to be considered. News reports only document a part of the illegal trade and cannot be considered an exhaustive dataset of the same, as not all incidents are documented. Additionally, seizure reports only indicate enforcement-detected wildlife crime events. Effective enforcement may also result in a higher number of IWT seizures from specific regions, which may not be regions that observe high wildlife crime. Enforcement agencies are likely to detect certain species of wildlife and their derivatives more than others. There may also be biases in reporting high-profile species than those involving lesser-known species. Nonetheless, media articles continue to be a valuable source of information on the species traded, volumes involved and the overall nature of the trade.

The maximum number of incidents reported were of ungulates (89 incidents), followed by big cats (82 incidents), and pangolins (72 incidents). It also reported a significant number of crime incidents involving tortoises and freshwater turtles (61 incidents), elephants (57 incidents), red sandalwood (52 incidents), other reptiles (49 incidents), birds (37 incidents), and marine wildlife (35 incidents). Fewer IWT media reports were observed between March and May (average of ~35 incidents per month), in comparison to other months with an average of ~44 incidents per month.

In addition, 13 seizure incidents involved non-native or exotic wildlife, mostly along the international borders in West Bengal and northeast India, and at airports (two records from Chennai and one from Kolkata). Media reports concerning elephant poaching suggest that 60 kg of elephant ivory was stashed along the Indo-Bhutan border, with one incident documenting a seizure of 16 kg of elephant tusks, which were to be smuggled after the ease of COVID lockdown restrictions.

Reports of big cat-related crime incidents were often of them trapped in snares. In some of these cases, the big cats were found mutilated, and certain body parts extracted from their carcasses. While a majority of the incidents documenting tortoise and freshwater turtles, particularly softshell turtles, involved the smuggling of live individuals, there were also seizures involving softshell turtle shells, meat and calipee (a fatty substance found in the lower shell of turtles and is considered as a delicacy). Despite the COVID-19 lockdown restrictions, data on lesser-known species like monitor lizard, sand boa, spiny-tailed lizard, and Indian chameleon was also steadily recorded. There were also cases of live and dead (scales-based) pangolin smuggling, and of a rhino poaching incident in May. Sea cucumber continued to remain the highest recorded marine species group in 2020, among incidents of illegal marine wildlife trade in India.

In recent years, illegal wildlife trade has been facilitated by online platforms, which are popular among sellers to advertise wildlife and arrange deals, due to the accessibility and privacy offered by such platforms. Online platforms were involved in multiple instances of illegal trade in 2020; for instance, YouTube was extensively used to advertise wildlife such as sand boa, tokay gecko and pangolin for sale. However, the involvement of online platforms in IWT cases is not an attribute of the pandemic or the related nationwide lockdown as many such cases have been documented in the past few years.

The WCS-India Counter Wildlife Trafficking (CWT) Programme aims to assist government agencies by providing access to information, skills, technology and expert support to tackle wildlife crime in India. The programme has been functional since 2019 and is run with the support of State Forest Departments, Wildlife Crime Control Bureau and other allied enforcement agencies that work on-ground to counter wildlife crimes in India.

The complete report can be accessed here: https://doi.org/10.19121/2021.Report.40773

References:

1. UNODC, World Wildlife Crime Report. 2020: Trafficking in Protected Species.

2. Van Uhm, D., South, N. & Wyatt, T. 2021. Connections between trades and trafficking in wildlife and drugs. Trends in Organized Crime 24, 425–446. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12117-021-09416-z

3. Mendiratta, U., Khanyari, M., Velho, N., Suryawanshi, K.R., Kulkarni, N. 2021. Key informant perceptions on wildlife hunting in India during the COVID-19 lockdown. https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.05.16.444344v1

4. Badola, S. Indian wildlife amidst the COVID-19 crisis. 2020. An analysis of the status of poaching and illegal wildlife trade. TRAFFIC, India.

CI is a non-profit, non-commercial portal that aims to facilitate wildlife and nature conservation by providing reliable information and the tools needed to campaign effectively.

CI is a non-profit, non-commercial portal that aims to facilitate wildlife and nature conservation by providing reliable information and the tools needed to campaign effectively.